Dr. Sabry A. El-khodary graduated from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Benha University in 1990, obtaining his PhD from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Kafr El-Sheikh University in 2000. In 2003, he received a personal grant from the European commission (TEMPUS program) as well as a grant from the German DAAD Organization in 2004. In 2007, he completed his Postdoctoral fellowship from the Japanese Matsumae international foundation, which was followed by another Postdoctoral fellowship at Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine (Japan) in 2008.

Having participated in teaching Veterinary Internal Medicine in Egyptian and Arab universities (Tripoli University), Dr. El-khodary has published 73 papers in international peer-reviewed journals and is currently a member of the scientific committee for the promotion of professors at the supreme university council in Egypt as well as coordinator of international agreements between the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Mansoura University and Liverpool University.

Prof. El-khodary, you have a prominent professional career in Veterinary Medicine, having focused on ruminant and equine species. What drove you to pursue research in this field?

Dear Mycotoxinsite readers, I would like to thank you for this opportunity to share some of my experience in mycotoxin research.

My research is focused mainly on ruminants and equines as a professor of Internal Medicine.

Fortunately, my dream started to come true when I obtained a fellowship at the Cattle Clinic at Hannover University, where I met highly renowned professors and was able to learn a lot from them. I obtained more experience and practice by collaborating with a Japanese school.

After that, more and more ideas for research have risen based on reading and observations and clinical problems. Many of my students have assisted me in executing my ideas and publishing many research articles.

What advice would you give the new generations of students and veterinarians that are thinking about following in your steps?

My advice to the new generations of students and veterinarians who are thinking about following in my steps is that everyone should have their own dream.

Be perseverant to achieve your dream, do not give up, be optimistic, and believe that you will succeed.

Be perseverant to achieve your dream, do not give up, be optimistic, and believe that you will succeed.

Traditionally, mycotoxin toxicity has been more associated with swine and poultry, considering that ruminant species were more “resistant” to the effects of these toxins. In your expert opinion, is this so? How does exposure to mycotoxins affect the health and productivity of these animals?

The starting point for mycotoxins to affect the health and productivity of animals is the induction of oxidative stress, hypoxia, decreased phagocytosis, and immunosuppression.

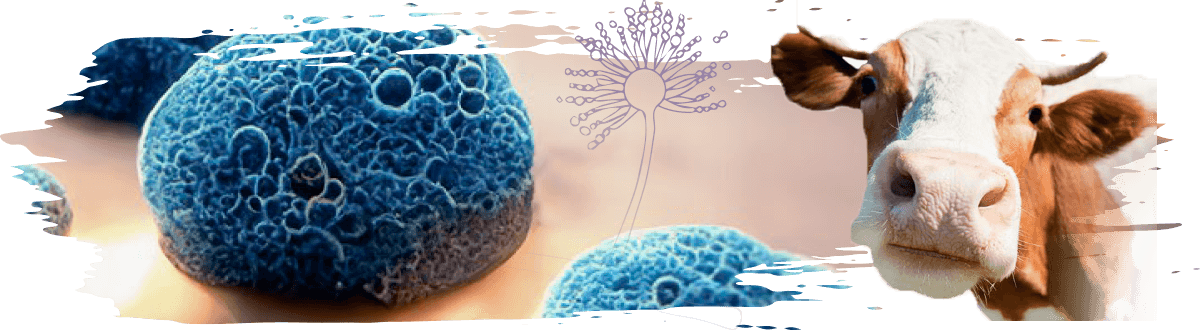

For example, A. fumigatus produces several mycotoxins, including tremorgens that are toxic to cattle.

For example, A. fumigatus produces several mycotoxins, including tremorgens that are toxic to cattle.

Gliotoxin, an immune suppressant, has been found in animals infected with A. fumigatus with a subsequent increase in its virulence.

⇰ It is probable that gliotoxin, T-2 toxin, or other mycotoxins that suppress immunity may be a trigger to the increased infectivity of this fungus, ultimately resulting in hemorrhagic bowel syndrome or other fungal infections.

Mycotoxins can negatively affect intestinal integrity, which acts as a physical barrier preventing the passage of pathogens and toxins. Furthermore, they also increase permeability and reduce intestinal cell viability.

Mycotoxins can negatively affect intestinal integrity, which acts as a physical barrier preventing the passage of pathogens and toxins. Furthermore, they also increase permeability and reduce intestinal cell viability.

Mycotoxins also affect the gut microbiota by causing an imbalance in the bacterial population.

Mycotoxins also affect the gut microbiota by causing an imbalance in the bacterial population.

⇰ They decrease the beneficial bacterial population and increase the pathogenic bacterial population. Therefore, regarding the aforementioned pathway, varying degrees of clinical illness occur.

Moreover, mycotoxins cause damage to the liver, consequently influencing the animal’s detoxification capacity.

Moreover, mycotoxins cause damage to the liver, consequently influencing the animal’s detoxification capacity.

As a specialist in Internal Medicine, which are the main mycotoxins you encounter in your daily practice and what are the symptoms that usually make you suspect this kind of problem?

From the clinical point of view, aflatoxins are the most predominant type of mycotoxins encountered in cattle practice.

Dairy and beef cattle are more susceptible to aflatoxicosis than the other species.

- ⇰ Young animals are more susceptible to the effects of aflatoxins than mature animals.

- ⇰ Gestating and growing animals are less susceptible than young animals but more susceptible than mature animals.

Toxicity due to aflatoxins, under natural conditions, is usually subacute or chronic, depending on the level of exposure.

When tackling a possible situation of mycotoxin exposure in ruminant species, which are the steps you recommend in order to identify the problem and remediate the effects of these toxins?

The following steps are recommended to identify the problem and to remediate the effects of these toxins:

|

The inclusion of mycotoxin adsorbents is a common practice in animal production. Do you have experience with these compounds?

Sure, we have experience with mycotoxin adsorbents in the field.

Commercial products that adsorb mycotoxins or cause biotransformation (non-pathogenic yeast) are highly effective in clinical practice.

Commercial products that adsorb mycotoxins or cause biotransformation (non-pathogenic yeast) are highly effective in clinical practice.

Some research has highlighted that mycotoxins and endotoxins together may have synergistic effects that may increase their overall negative impact on animal health and production. Have you observed this relationship? Do you think that the use of adsorbents can also be a way to tackle the presence of endotoxins in the animals’ intestinal tract?

In a study on ill-thrift in buffalo calves, we found an association between the type and quality of concentrate and ill-thrift.

Firstly, we know that mycotoxins negatively influence intestinal integrity, which acts as a barrier preventing the passage of pathogens and toxins.

Some mycotoxins decrease the production of mucins and damage the tight junctions. They can also affect intestinal cell viability and reduce cell proliferation, leading to a reduced capacity of the intestine to repair.

⇰ This increased permeability of the intestinal epithelial layer promotes the leakage of not only mycotoxins but also endotoxins into circulation. Once in circulation, mycotoxins increase the sensitivity to endotoxins and vice versa, reducing the minimum dose needed to generate an inflammatory response and exert toxic effects in different organs.

Moreover, mycotoxins can damage liver tissue, which is responsible for the detoxification of many hazardous compounds including endotoxins.

Susceptibility to infections is a global problem in the livestock industry, especially in the context of zoonotic diseases and the development of antimicrobial resistance. Keeping in mind the importance of reducing the use of antimicrobials and relying on other strategies, such as vaccination, do you think that mycotoxins receive sufficient attention as risk factors for immunosuppression that can make animals more susceptible to infections and may not respond as well to vaccination protocols?

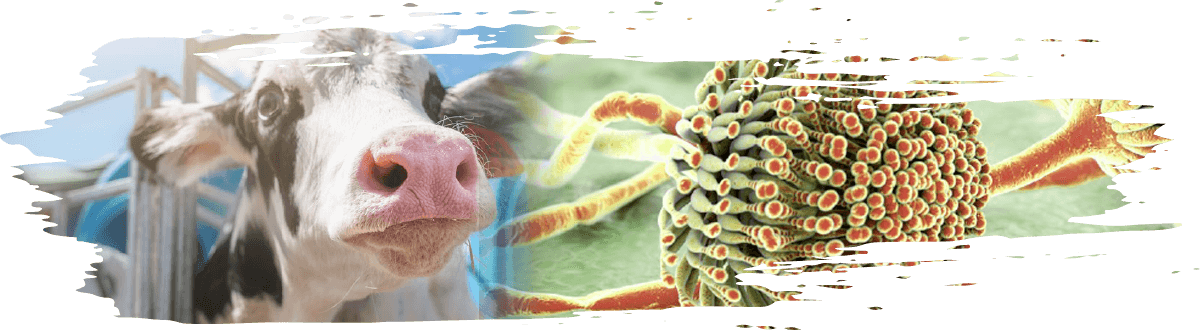

Recent studies confirm that mycotoxins induce oxidative stress, hypoxia, and immunosuppressive effects. Moreover, emerging evidence shows that mycotoxins have the potential of inducing cellular senescence, which is involved in immunomodulatory functions.

![]() Increased susceptibility to infection caused by mycotoxins has been documented in both experimental and natural conditions.

Increased susceptibility to infection caused by mycotoxins has been documented in both experimental and natural conditions.

![]() In calves, aflatoxins increase the susceptibility to E. coli EPEC/EHEC.

In calves, aflatoxins increase the susceptibility to E. coli EPEC/EHEC.

![]() In pigs, FB1 increases the susceptibility to P. multocida, E. coli ETEC/EPEC, and S. typhimurium, as well as inhibiting lymphocyte cell proliferation and altering cytokine production.

In pigs, FB1 increases the susceptibility to P. multocida, E. coli ETEC/EPEC, and S. typhimurium, as well as inhibiting lymphocyte cell proliferation and altering cytokine production.

Aflatoxin B1 increases the synthesis of IFN-gamma, a Th1 cytokine involved in the cell-mediated immune response, and decreases IL-4 synthesis, a Th2 cytokine involved in the humoral response.

⇰ This alteration of lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production might explain the failures in vaccination observed in vivo.

![]() The presence of mycotoxins in the feed may lead to a breakdown in vaccinal immunity and the occurrence of disease even in properly vaccinated groups.

The presence of mycotoxins in the feed may lead to a breakdown in vaccinal immunity and the occurrence of disease even in properly vaccinated groups.

In addition to the abovementioned effects, the effect of mycotoxin intoxication on drug efficacy has also been documented in poultry.

⇰ For example, contamination of feed with various doses of T-2 toxin significantly reduced the anticoccidial efficacy of lasalocid in chickens. Consequently, there was an increase in the mortality rate and the development of more lesions.

What would you like your take-home message to be our readers?

Mold exists as long as there is life and, thus, mycotoxins. This is why we must fight mycotoxins all the time.

Micotoxicosis prevention

Micotoxicosis prevention