Marta Jaramillo is a Veterinarian with a MSc degree in Poultry and Swine Production Systems and Doctorate in Agricultural Science. Having received her education as a Scientific Researcher at the National Agricultural Research Institute (Fondo Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias – FONAIAP-Venezuela), she has more than 30 years of experience structuring, conducting and developing basic and applied poultry research projects, having worked in the field of Mycotoxicology during the last 28 years. Since 2005, she has been working as an Independent consultant in Poultry Integration Systems and Animal Feed Mills in Venezuela, as well as at an International level.

YOU HAVE SPECIALIZED IN THE STUDY OF MYCOTOXINS AND THEIR EFFECTS ON POULTRY HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE. IN YOUR OPINION, WHICH ARE THE MAIN MYCOTOXINS THAT CURRENTLY POSE A THREAT TO POULTRY IN YOUR REGION?

Your question is very important, but to respond, I should emphasize that currently, we cannot speak about mycotoxins detected individually in raw materials as there is a very high probability of finding two or more mycotoxins as natural contaminants in these materials, or in a certain food, and this is something that occurs in the real world.

-

⇰ On one hand, we must always consider that different genera of toxicogenic molds appear simultaneously in nature as natural contaminants, producing different types of mycotoxins.

-

⇰ On the other, we must keep in mind that the presence of just one genus of mold with potential toxicogenicity can be enough to produce several mycotoxins.

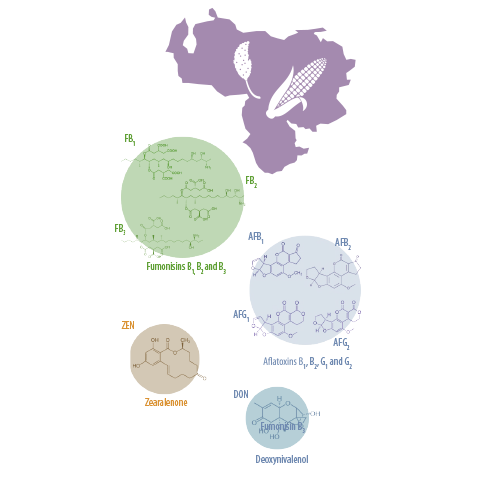

Based on this reality, during the last 10 years, I have observed that the results of the analysis of corn (Zea mays), grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench) produced in Venezuela and in imported corn reveal a trend towards an increase in the incidence of fumonisins B1 and B2 that contaminate these substrates, normally together with aflatoxins, which makes it worthy of noting that the these continue to be very harmful to poultry.

Deoxynivalenol (DON) and Zearalenone are also present, but with a lower incidence.

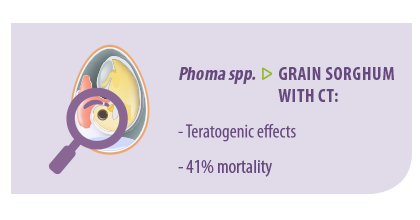

Additionally, in studies that we have conducted in grain sorghum containing condensed tannins (CT), we have isolated the mold Phoma spp. that produces unidentified toxic metabolites capable of producing teratogenic effects and up to a 41% of embryonic mortality in poultry during the incubation phase.

HAVE YOU SEEN A CHANGE REGARDING THE OCCURRENCE OF THESE MYCOTOXINS COMPARED TO THE PAST? IF SO, COULD THIS BE DUE TO CLIMATE CHANGE OR HUMAN ACTION?

At a global level, there have been some interesting changes regarding the mycotoxins with the highest incidence found in the field as natural contaminants.

In the case of Venezuela, we have observed that the mold Fusarium verticillioides, formerly known as Fusarium moniliform, widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas and with the toxicogenic potential to produce fumonisins B1, B2, and B3, has shown a high incidence in corn and grain sorghum with and without CT. In Venezuela and other countries, these cereals are the basic ingredients for the formulation of feed destined for use in breeders, broilers, and layers.

However, in Venezuela, the mold Aspergillus flavus, capable of producing aflatoxins, continues to appear with a high incidence and simultaneously with F. verticilloides, as a contaminant in these cereals.

This is something to be discussed another time so as not to move away from the subject at matter. In any case, I would like to leave you with this conundrum, that should not be forgotten because it is what we should focus on if we want to interpret the clinical cases in the field.

Furthermore, among these changes, we have also observed a higher amount of fungal mycobiota, expressed in the percentage of internally colonized grains where we have quantified total molds, genera and some species of molds, in grain sorghum containing CT.

Among these genera Phoma spp., Fusarium spp., Aspergillus spp., Curvularia spp., Colletotrichum spp. and Eurotium spp.have the highest incidence.

Additionally, in many cases, we have observed that the concentration of total aflatoxins currently exceeds 20 μg/kg in sorghum with TC. This contrasts with the low, very low or no aflatoxins found in sorghum in the ‘80s and ‘90s, which is a clear evidence of change.

On the other hand and regarding your question, I consider that the Climate Change we have and are experiencing has influenced, and will continue to directly influence the changes in the frequency occurrence of mycotoxins that we already know, as well as the emergence of new fungal metabolites with unknown potential toxigenicity.

Additionally, human action has also played a role. With or without knowing their drastic consequences, humans due to Climate Change, have adopted inadequate measures for managing plants in agricultural processes and, among these, I would like to highlight inappropriate use of insecticides and fungicides.

Thus, the macro- and micro-environmental conditions, the nutrient profile and the ecosystem, including the soil microbiota and macrobiota, have been affected in such a way that we have lost the balance among this trinomial.

These two realities that we are subjected to at a global scale, Climate Change and Human Action, have been decisive in triggering mechanisms in the soil microbiota and macrobiota that can be associated with genetic mutations that ensure their survival when faced with an inadequate nutrient profile and a suboptimal and unbalanced micro- and macro-environment.

This means the appearance of new communities of molds in the field and with them, the production of new toxic metabolites or mycotoxins that were unknown until now also occurs.

- ⇰ In this regard, poultry could show clinical manifestations and necropsy findings that differ from those produced by known mycotoxins.

- ⇰ It could also be expected that the progressive increase in temperature will probably lead to the appearance of new genera of molds or strains of potentially toxigenic Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium adapted to living in these new micro- and macro-environmental conditions.

Finally, to conclude this point, I would like to invite you to read a document edited by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), titled “Strategy of the FAO on the Climate Change”, which exposed the dramatic effects of the climate change on agriculture, food safety, human nutrition, and feeding, among other topics.

Finally, to conclude this point, I would like to invite you to read a document edited by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), titled “Strategy of the FAO on the Climate Change”, which exposed the dramatic effects of the climate change on agriculture, food safety, human nutrition, and feeding, among other topics.

ONE OF YOUR FIELDS OF INVESTIGATION HAS BEEN CONDUCTING A METHODOLOGY TO DETERMINE THE PRESENCE OF MYCOTOXINS IN BROILER HATCHING EGGS. COULD YOU BRIEFLY EXPLAIN WHAT THIS METHODOLOGY CONSISTS OF AND THE OBJECTIVE OR PRACTICAL APPLICATION IT HAS?

![]() This methodology is based on a procedure reported by the AOAC (1984) and modified by Wyatt y Jaramillo (2002) and it consists in carrying out toxicity biological trials using broiler chicken embryos incubated until the end-stage (21 days). I would summarize this procedure in six stages:

This methodology is based on a procedure reported by the AOAC (1984) and modified by Wyatt y Jaramillo (2002) and it consists in carrying out toxicity biological trials using broiler chicken embryos incubated until the end-stage (21 days). I would summarize this procedure in six stages:

1. Selection of a sterile substrate (corn, sorghum, rice, wheat, barley, etc.). To obtain the pure mold culture, the sample is incubated in sterile conditions.

2. Extraction of metabolites found in the pure mold strains obtained in stage 1.

3. Incubation of uniform weight SPF hatching eggs (Specific Pathogen-Free). 72 hours postincubation a candling procedure is carried out, discarding and replacing any abnormal eggs.

4. Establishment of the experimental treatments and inoculation of the embryonated eggs with the mold metabolites obtained in stage 2.

Inoculation of the egg is carried out 72 hours post-incubation. Each treatment is replicated in at least 20 eggs with the metabolites obtained from a pure mold strain.

5. Incubation until end-stage in the hatcher with controlled temperature and humidity, as well as an automatic rotation device.

Additionally, it is essential to incorporate control groups to the assessed treatments as follows:

A. NEGATIVE CONTROLS:

Non-inoculated eggs: that is to say, intact eggs as a control of the group of breeders from which they were obtained.

Non-inoculated eggs: that is to say, intact eggs as a control of the group of breeders from which they were obtained. Eggs inoculated with the extraction solution.

Eggs inoculated with the extraction solution. Eggs inoculated with an extract of the substrate in sterile conditions and without inoculating. It should be noted that this negative control must be repeated for all the substrates that are used.

Eggs inoculated with an extract of the substrate in sterile conditions and without inoculating. It should be noted that this negative control must be repeated for all the substrates that are used.

B. POSITIVE CONTROL:

Eggs inoculated with an extract of the mold strain with high potential toxicity obtained in previous studies.

Eggs inoculated with an extract of the mold strain with high potential toxicity obtained in previous studies.

6. At the end of the experiment (21-22 days), the percentage of mortality is calculated and the non-hatched embryos are examined to verify possible teratogenic effects.

Therefore, and keeping in mind that sophisticated equipment is not required for their practical application, except for a correctly functioning hatcher, I consider that it is a valuable methodology and experimental tool for these kinds of studies.

YOU HAVE ALSO CARRIED OUT STUDIES ON DIFFERENT KINDS OF INTERACTIONS THAT OCCUR BETWEEN DIFFERENT MYCOTOXINS. KEEPING IN MIND THAT, IN MOST CASES, A SINGLE RAW MATERIAL MAY BE CONTAMINATED WITH SEVERAL MYCOTOXINS, ARE THERE SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCES IN COMPARISON WITH SITUATIONS IN WHICH THERE IS A SINGLE MYCOTOXIN? WHICH SIGNALS, IN RAW MATERIALS OR POULTRY, THAT COULD MAKE US THINK THAT WE THERE IS A SITUATION OF CONTAMINATION WITH MULTIPLE MYCOTOXINS?

Many veterinarians, professionals, and producers that work in the poultry industry ask me this question to understand the effects of mycotoxicosis that are associated with the presence of two or more mycotoxins contaminating the raw materials or feed.

I always say that, before giving a diagnosis, we should carry out a detailed evaluation of the events that might have happened throughout the agro-industrial chain. This implies scrutinizing, in each step, starting in the field, with the cultivation of the raw materials, and ending with the findings from the processed birds.

As professionals, we should be critical, understanding that there are many other causes and pathologies that can affect bird health and that they can manifest with symptoms and alterations that are similar to the ones produced by mycotoxins.

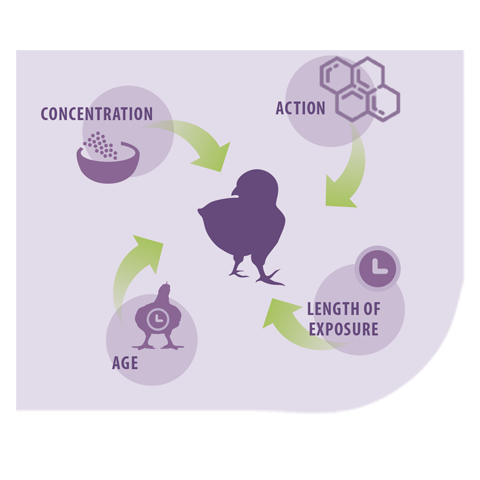

Additionally, it is important to keep in mind that often, despite the existence of multiple mycotoxins contaminating the raw materials and feed, the interaction between them doesn’t always occur and, in this case, the effect and the birds’ response will mainly depend on:

- ⇰ The action of the mycotoxin with the highest toxicogenic potential.

- ⇰ Its concentration in the feed.

- ⇰ The length of exposure to the mycotoxin.

- ⇰ The bird’s age.

TOXICOLOGICAL PRINCIPLES:

Knowing the toxicological principles that govern the interactions between mycotoxins. These are:

1.Principle of Additivity: in this case, there are interactions that lead to the addition of the effects of the mycotoxins.

The principle of Additivity implies that the effect that results from the action of two or more mycotoxins is the same as the sum of the individual effect of each mycotoxin.

In poultry, this additive effect has been observed between:

Aflatoxin and DON.

Aflatoxin and DON. Aflatoxin and cyclopiazonic acid (CPA),

Aflatoxin and cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), Aflatoxin and moniliformin.

Aflatoxin and moniliformin. Fumonisin B1 and toxin T2.

Fumonisin B1 and toxin T2. ACP and ochratoxin A.

ACP and ochratoxin A. Aflatoxin and diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS).

Aflatoxin and diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS).

![]() This kind of interaction has been frequently observed in poultry exhibiting confusing symptoms.

This kind of interaction has been frequently observed in poultry exhibiting confusing symptoms.

2.Principle of Synergy: in this case, there are interactions that lead to synergic effects among mycotoxins.

The principle of Synergy implies that the effect that results from the action of two or more mycotoxins is greater than the sum of the individual effect of each mycotoxin.

In poultry, it is especially notable to observe the synergy between:

Aflatoxin and ochratoxin A.

Aflatoxin and ochratoxin A. Aflatoxin and toxin T2.

Aflatoxin and toxin T2. Aflatoxin and DAS.

Aflatoxin and DAS.

When faced with a synergic interaction, it is difficult to make a quick and precise diagnosis of the problem.

3. Principle of Antagonism: in this case, there are interactions that lead to antagonistic effects among mycotoxins.

The principle of Antagonism implies that the effect that results from the action of two or more mycotoxins is less than the sum of the individual effect of each mycotoxin.

This antagonistic interaction has been observed between:

Ochratoxin A and citrinin.

Ochratoxin A and citrinin. Ochratoxin A and DON.

Ochratoxin A and DON. Ochratoxin A and DAS.

Ochratoxin A and DAS. Aflatoxin and DAS.

Aflatoxin and DAS.

In this case, the action of one mycotoxin antagonizes the action of the other, mitigating the adverse effect.

In this regard, I would like to highlight the antagonistic action that citrinin has on ochratoxin A, minimizing the adverse effect that ochratoxin A has on weight gain.

REPRESENTATIVE SAMPLING

Analysis of the corn and other cereal grains used in the production of feed must be based on a representative SAMPLING of the batch to be used.

This is fundamental because if the sample is not representative, we will not obtain reliable results and we could end up considering the raw material to be negative whereas in reality, it is contaminated with mycotoxins.

![]() Usually, apart from the mycotoxins analysis, I carry out a mycological analysis of the cereals to determine the genera of the molds that have internally colonized the grains in the field, as well as the fungal load that has been added during storage, which allows us to link them to their possible toxicogenic potential.

Usually, apart from the mycotoxins analysis, I carry out a mycological analysis of the cereals to determine the genera of the molds that have internally colonized the grains in the field, as well as the fungal load that has been added during storage, which allows us to link them to their possible toxicogenic potential.

If the results reveal the presence of two or more mycotoxins, even at small concentrations, it is enough to alert us of any eventuality in the field.

THE VETERINARIAN’S CLINICAL EYE

The field veterinarian’s clinical eye is fundamental.

In this regard, a detailed macroscopic evaluation of the organs and tissues during necropsy, the production rates, the birds’ behaviour, their physical appearance and their age are basic factors to keep in mind when reaching a presumptive diagnosis of mycotoxicosis.

However, necropsy findings and the analysis of flock history will orient us towards the implementation of measures and controls against the problem.

REGARDING THE STUDIES YOU HAVE CONDUCTED ON THE EFFECTS OF MYCOTOXINS IN BROILER CHICKENS, WHICH ARE THE MOST SIGNIFICANT RESULTS THAT YOU WOULD HIGHLIGHT WHEN IT COMES TO DIGESTIVE CAPACITY?

![]() Several studies that we have carried out reveal very interesting results, allowing us to explain many acute, sub-acute and chronic clinical events that occur in broiler chickens.

Several studies that we have carried out reveal very interesting results, allowing us to explain many acute, sub-acute and chronic clinical events that occur in broiler chickens.

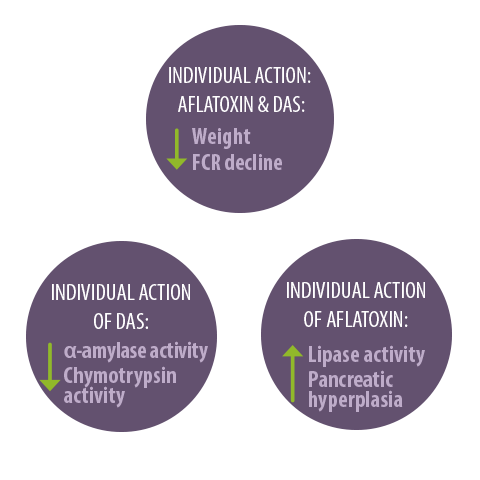

However, answering your question, I would like to highlight the results of a study in which we assessed the effects of aflatoxin and DAS, administered individually and combined, on the pancreatic exocrine function of broilers fed with a diet contaminated with these mycotoxins during their first 21 days of life.

The effects were measured by determining pancreatic enzyme activity (α-amylase, lipase, trypsin, and chymotrypsin), pancreatic size, the number of zymogen granules, the number of pancreatic acinar cells, among others.

![]() We were able to observe that the mycotoxins, when administered individually, affected the activity of some of these enzymes:

We were able to observe that the mycotoxins, when administered individually, affected the activity of some of these enzymes:

- ⇰ Aflatoxin significantly increased the enzymatic activity of lipase, whereas DAS reduced the activity of α-amylase and chymotrypsin in comparison to the control groups that received a mycotoxin-free diet.

- ⇰ Aflatoxin significantly increased the pancreatic size in comparison with the control birds and those that received a diet contaminated with DAS.

The increase in the pancreatic size could be a result of the birds’ compensatory physiological response aimed at counteracting the aflatoxin’s adverse effects. It was a consequence of the hyperplasia that manifested with an increase in the number of zymogen granules and pancreatic acinar cells.

The loss of the pancreatic enzyme activity, due to the individual effects of aflatoxin and DAS, was reflected in the birds with lower weights and a decline in their feed conversion.

Combined administration of both mycotoxins revealed an effect associated with aflatoxin consisting of an increase in the lipase activity and the development of pancreatic hyperplasia. These effects had been observed in chickens fed with a diet contaminated only with aflatoxin.

In this study, the analysis of the pancreatic enzyme activity did not show interactions between the mycotoxins. This implies that the altered fat digestion can be attributed to the aflatoxin’s action, whereas the alterations in the digestion of carbohydrates and proteins occur in cases of individual contaminations with DAS.

Based on these results, it is possible that, when birds are exposed to these mycotoxins for longer periods, the pancreatic enzyme activity may be affected to a greater extent, seriously impairing their digestion.

WE HAVE INCREASING AMOUNTS OF INFORMATION FROM THE ANALYSIS OF MYCOTOXINS IN RAW MATERIALS DESTINED TO ANIMAL FEED. HOW CAN WE PROCESS ALL THIS INFORMATION TO USE IT IN A PRACTICAL WAY AND TO PREVENT FUTURE CONTAMINATION?

First of all, it is important to understand that mycotoxin contamination occurs naturally in the field. Soil, among its microbiota, contains a fungal load that will contaminate the plants by colonizing them from the inside.

In general, in the case of cereal grains, we have isolated a wide range of molds, including genera that are potentially toxicogenic, in freshly harvested grains before storage.

In this scenario, it is crucial to minimize the risk of contamination of the raw materials with recurring mycotoxins.

Therefore, programs and technologies that allow us to carry out an integral analysis of the mycotoxin challenge all year-round are basic tools when facing this problem.

Following these guidelines requires working with the expert criteria of the professionals that are responsible for Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC). Currently, QA/ QC procedures must be implemented throughout the entire agro-industrial chain involved in poultry production that starts in the field, harvesting and buying the raw materials for feed production, and ends, in the case of broiler production systems, at the processing plants.

However, it should be noted that other poultry production systems, such as breeder and layer systems, also need to follow QA/QC procedures, continuously to monitor every link involved in these production systems.

This will allow us to compile a Database containing all information from the analysis of the raw materials, as well as the findings that are recorded throughout this chain.

This integral management strategy will make us more efficient for preventing the mycotoxins contamination during different stages, which means that we will be more efficient in preventing mycotoxicosis in the field.

I would like to stress the role of the QA/QC Manager in feed mill, that must coordinate the sampling operations for the raw material pre-purchase, during the reception and storage of the raw materials and for the final product. When it comes to storage, it’s important to establish a systematic sampling program that includes the raw material storage time to obtain reliable results.

This way, we can obtain the above-mentioned Databases with the results that will allow the specialist to:

- 1. Define the procedures and nutritional practices that contribute to mitigating the effects of mycotoxins in poultry.

- 2. Select the best binders with adsorbent capacity aimed at the mycotoxins that appear most frequently.

- In addition to this, define the dosage of the adsorbent according to the level of contamination shown by the historical record and define the administration stage or stages during the birds’ life.

- 3. Define the poultry management practices at the farms.

- 4. Define the raw material and feed management practices at high-risk contamination points.

YOU HAVE PARTICIPATED IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION OF QUALITY ASSURANCE AND QUALITY CONTROL MODELS AND PROCEDURES TO MINIMIZE THE RISK OF CONTAMINATION OF RAW MATERIALS WITH MYCOTOXINS. COULD YOU EXPLAIN, FROM A PRACTICAL POINT OF VIEW, WHICH ARE THE CRITICAL CONTROL POINTS TO KEEP IN MIND FROM HARVEST TO FEEDING THE ANIMALS?

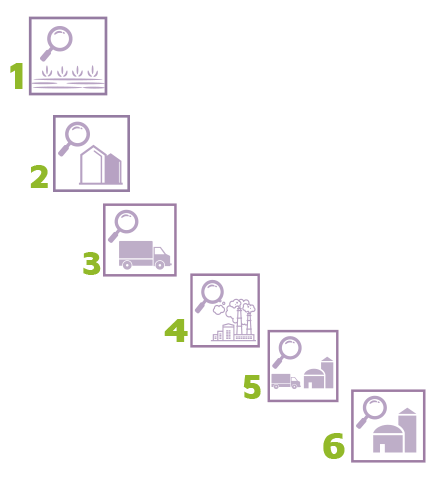

First of all, I would like to newly point out that it is currently not possible to completely eliminate the contamination of raw materials (cereals and oilseeds) with mycotoxins, but it is possible to adopt practices aimed at reducing the occurrence of this contamination and, therefore, the risk that the presence of these toxic metabolites pose to human and animal health.

Responding to your question in a comprehensive manner, we should also keep in mind the critical control points (CCPs) that are present before harvesting the raw materials, as these are the first points involved in fungal contamination and mycotoxin production.

In this regard, part of the prevention strategy in the agro-industrial poultry production chain should include programs based on good agricultural practices (GAPs), good hygiene practices (GHPs), and good manufacturing practices (GMPs) at the following CCPs:

1. At the field level:

En la etapa de preparación del suelo para la siembra de los cultivos.

- ⇰ During the soil preparation stage before planting crops.

- ⇰ During the pre-harvesting stage.

- ⇰ During harvesting, collection, and drying of the raw materials.

2. During the storage of the raw materials in commercial silos.

3. During the transportation of raw materials from storage facility (commercial silos) to the feed mill.

4. During the storage of the raw materials at the feed mill.

5. During the transportation of the finished product from feed mill to farms.

6. During the feed storage at farms.

To finish answering your question, I would like to highlight that in each of these CCPs, there is a series of measures, preventive and corrective management programs that, if completely fulfilled, will determine our success in the pursuit of set goals: “reducing the risk of mycotoxin contamination of raw materials used in the preparation of feed for poultry and other animals, as well as for humans”.

IN YOUR OPINION, WHICH ARE THE MAIN POINTS THAT FEED MANUFACTURERS SHOULD FOCUS ON TO PREVENT THE CONTAMINATION OF THEIR RAW MATERIALS AND FINISHED PRODUCTS WITH MYCOTOXINS? AND IN THE CASE OF POULTRY PRODUCERS?

In today’s world, amid the 21st century, with the increasing challenges that we are faced with when producing innocuous food for human and animal consumption, it is essential to develop highly specialized QA/QC Programs that should be firmly implemented and completely fulfilled.

Therefore, both animal feed manufacturers and poultry producers at a farm level should focus on structuring and developing a Quality Assurance and Quality Control Management System that includes the implementation of a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points program (HACCP). It is a vital tool for identifying, assessing and controlling the risk of contamination of raw materials and feed, not only with mycotoxins but also with bacteria and other pathogenic microorganisms that seriously compromise food safety and, therefore, human and animal health

HACCP is a key tool for QA/QC management systems and to be implemented it is fundamental to follow these principles:

Carry out a risk assessment.

Carry out a risk assessment. Determine the CCPs.

Determine the CCPs. Establish the critical limits.

Establish the critical limits. Establish the monitoring system to guarantee the control of each CCP.

Establish the monitoring system to guarantee the control of each CCP. Establish corrective measures.

Establish corrective measures. Establish verification procedures.

Establish verification procedures. Establish record-keeping procedures.

Establish record-keeping procedures.

In my experience, I would highlight that the main CCPs at feed mills are found in the storage silos and storage facilities for the raw materials and the end products.

In poultry farms, they are mainly found in the bulk storage silos and the storage facilities for sacks of feed.

Another important CCP, both for feed mills and farms, is found in the vehicles that transport the end product from the feed mill to the poultry farms.

Micotoxicosis prevention

Micotoxicosis prevention