With a solid research career at the Complutense University of Madrid, Jéssica Gil Serna has established herself as one of the leading voices in the study of mycotoxigenic fungi and their impact on food safety.

As a professor and researcher at the Department of Genetics, Physiology and Microbiology, she is part of the group Fungi and Yeasts of Interest in Agri-Food, where she leads studies focused on species of the genus Aspergillus and Fusarium. Her work goes beyond the laboratory, combining basic research with practical applications to mitigate the presence of mycotoxins in food and feed.

With a clear vocation for dissemination and a critical view of the impact of climate change on fungal ecosystems, Jéssica represents a generation of scientists committed to sustainability, public health, and knowledge transfer.

In this interview, we explore the challenges, findings, and perspectives of her work on one of the most persistent and complex contaminants in the agri-food chain.

Jéssica, you started your research career in the field of mycology. What specifically attracted you to the study of mycotoxin-producing fungi?

We could say that I came into this field almost by chance.

When I was finishing my degree in Biology, it was clear that I loved microbiology and that this was the area in which I wanted to do research.

At that time, I met my two thesis supervisors who taught me how amazing fungi are and I have not been able to leave this world.

In several of your publications you point out that not all Aspergillus flavus produce aflatoxins. To what extent are we still overestimating or underestimating certain genera or species in terms of toxicological risk?

It is true that many strains of Aspergillus flavus are not capable of producing aflatoxins.

Some of them are even approved for use in certain countries to control the presence of toxigenic strains.

If we only mention the name of the species we could be overestimating the risk.

In many cases, strains are not able to produce aflatoxins because they have lost all or most of the genes involved in their synthesis.

Therefore, molecular techniques could be applied to test for the presence of these genes to get a clearer idea of their toxigenic potential.

Therefore, molecular techniques could be applied to test for the presence of these genes to get a clearer idea of their toxigenic potential.

Which geographical areas of Spain do you consider currently more vulnerable to the presence of mycotoxins and how has this map evolved with climate change?

am not clear on whether there are areas of Spain more or less vulnerable to mycotoxin contamination in general.

![]() What is clear is that mycotoxins are appearing in places and crops where they had never been detected before.

What is clear is that mycotoxins are appearing in places and crops where they had never been detected before.

Current evidence suggests that the fungi are moving towards more favorable areas under climate change.

Ten years ago, predictions indicated that Aspergillus flavus was going to become a serious problem in southern Europe, and indeed it is becoming so.

We are finding this fungus in more and more areas of Spain and it is contaminating a wider variety of crops.

What we need are studies on the incidence of toxigenic fungi in our country to have a clearer idea of the risks we face.

In products such as wine or cheese, the presence of fungi is part of the process. To what extent is the line between “fungi-friends” and “fungi-enemies” as thin as it seems?

It is clear that fungi are essential for the industry and the consumer must be reassured that food safety is guaranteed.

If they are used for food production, it is because they are totally safe.

If they are used for food production, it is because they are totally safe.

However, sometimes other undesirable molds appear in our homes that can produce mycotoxins and put our health at risk.

For example, a Brie or Cammembert cheese is produced thanks to fungi of the Penicillium genus that form the white crust that surrounds them.

These fungi are “friends” and must be there. However, our “enemies” can also appear growing on the cheese paste.

There is where we should be careful and if we see mold on the inside, we should discard the product. The same would apply, for example, to cured meats. The fungi in the rind help curing, but if they appear in the cut, it is better to discard the product.

Some mycotoxins have complex chemical structures and bioactive effects. Is there a potential for positive reuse, e.g. in pharmacology?

So far, the scientific community is too preoccupied with getting rid of mycotoxins and not many studies have looked at their potential from a more positive point of view.

It is true that there are toxic compounds that used in controlled doses can be beneficial in treating diseases.

⇒ For example, some mycotoxins have demonstrated antitumor or immunosuppressive properties but their potential clinical application is still a long way off.

From your teaching experience, do you think that future professionals in the agri-food sector receive sufficient training on mycotoxins?

I believe that, in general, there is not enough training on mycotoxins at any stage of formal training.

In many cases, a few hours (even minutes) are devoted to mentioning what they are or which fungi produce them, but there is no in-depth explanation of their importance or what kind of strategies are available to control their presence in food.

![]() To be trained on these issues, some professionals take complementary courses and thus acquire knowledge on how to mitigate the effects of mycotoxins in the food chain.

To be trained on these issues, some professionals take complementary courses and thus acquire knowledge on how to mitigate the effects of mycotoxins in the food chain.

Your work mentions the use of non-toxigenic strains as a biocontrol strategy. What are the main challenges for these solutions to be implemented on an industrial scale?

The use of non-toxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus for the control of toxigenic strains is already a reality.

This type of product is being applied in different countries in Africa and in the United States in corn, cotton, and nut crops.

![]() They have been shown to bring great advantages, as they reduce the concentration of aflatoxins in the final product.

They have been shown to bring great advantages, as they reduce the concentration of aflatoxins in the final product.

![]() However, in Europe we are very cautious and the use of these organisms is prohibited and is not expected to be approved soon.

However, in Europe we are very cautious and the use of these organisms is prohibited and is not expected to be approved soon.

Although many studies have been carried out on their safety, there are still certain sectors of the scientific community that have doubts as to whether these strains could recover the capacity to produce aflatoxins.

If this were possible, we would be faced with a major problem, since we would have highly competitive strains that can also produce aflatoxins.

If this were possible, we would be faced with a major problem, since we would have highly competitive strains that can also produce aflatoxins.

Today it seems like science fiction, but fungi never cease to surprise us, so we must be careful.

What role do fungal species interactions play in mycotoxin production in the field or in storage?

That is one of the million-dollar questions in our field.

Fungi do not live alone in the environment and any microorganism in the environment could be affecting mycotoxin production.

However, to this day we still have a query to resolve before we can answer this question….

![]() Why do fungi produce mycotoxins?

Why do fungi produce mycotoxins?

Some authors consider that mycotoxins have a fundamental ecological role, as they could be antimicrobials that help the producing species to get rid of their competitors and to colonize the niche.

There is still much to be studied in this field…

What we do know is that some microorganisms can reduce fungal growth and mycotoxin production when applied directly to crops or during storage.

⇒ This is what we know as biological control agents and they can be a great alternative to the use of fungicides to control toxigenic fungi.

Are there any “minor” or understudied mycotoxins that you are particularly concerned about because of their potential impact?

Without a doubt, toxins produced by species of the genus Alternaria.

Until recently they were largely unknown, but recent studies have shown that they are very present in food and that their toxic effects may be much more serious than previously thought.

A few years ago, the European Union called on the scientific community to increase the number of studies related to them and it is expected that in a short time there will be a regulation governing their maximum levels in a wide variety of foods.

Do you think the general society is aware of the real risk posed by mycotoxins in their daily diet?

Not at all. I always say that mycotoxins are the great unknown in food safety.

Mainly because we are lucky enough to live where we live, where European regulations guarantee that the food that reaches the market is safe.

Of course, once the product reaches our homes, if we put ourselves at risk, it’s our own business.

I feel like a broken record always repeating that we cannot remove the moldy part of a product and eat the rest because we may be exposing ourselves to large amounts of mycotoxins.

![]() However, I think I still have to do it because people are still surprised, as they say it is something “that has been done all my life and nothing has ever happened”.

However, I think I still have to do it because people are still surprised, as they say it is something “that has been done all my life and nothing has ever happened”.

I believe that this lack of knowledge is due to the mode of action of mycotoxins.

Consuming contaminated food generally does not produce immediate symptoms as do other biological hazards that cause vomiting, diarrhea, malaise, etc.

⇒ Mycotoxins accumulate in the organism, producing a chronic intoxication that can have long-term effects, including the development of tumors.

We must convey to society that this is not a laughing matter.

Are we prepared to anticipate how future agricultural practices (such as agroecology or vertical farming) may change the mycotoxicological landscape?

It is clear that modern agriculture is tending towards more sustainable practices so, whether we want to or not, we have to be prepared to be able to anticipate possible new risks.

Different studies indicate that some agroecological practices such as crop rotation or biological control of diseases and pests can be very suitable to avoid mycotoxin contamination.

Different studies indicate that some agroecological practices such as crop rotation or biological control of diseases and pests can be very suitable to avoid mycotoxin contamination.

In other cases, contradictory results have been observed, for example, in the maintenance of a vegetative cover.

If well managed, it improves the soil microbiota, allowing it to compete effectively with mycotoxinproducing fungi, displacing them from the ecosystem.

If well managed, it improves the soil microbiota, allowing it to compete effectively with mycotoxinproducing fungi, displacing them from the ecosystem.

However, a poorly managed cover crop significantly increases soil moisture, providing ideal conditions for fungal growth.

However, a poorly managed cover crop significantly increases soil moisture, providing ideal conditions for fungal growth.

As far as I know, there are no studies that indicate whether vertical cultivation can be beneficial to control the presence of mycotoxins.

As it is an indoor environment, it allows control of environmental conditions, which would lead one to think that the development of toxigenic fungi could be better prevented. However, until there are exhaustive studies, it is difficult to say anything.

You are an active science communicator, how do you perceive the interest of the general media and the public in mycotoxin-related topics?

We have already mentioned that the subject of mycotoxins is very unknown by consumers and something similar happens in the case of the media.

We always see on TV when there are outbreaks of salmonellosis or listeriosis because they affect many people. However, it is rare to see mycotoxins discussed in the news, both in the written press and on television.

We always see on TV when there are outbreaks of salmonellosis or listeriosis because they affect many people. However, it is rare to see mycotoxins discussed in the news, both in the written press and on television.

Let’s say that nowadays mycotoxins are not mediatic.

And it is not because there are no RASFF reports every day indicating that batches of nuts, cereals or spices have been stopped at the border or withdrawn from the market because they greatly exceed the limits established by the European Union.

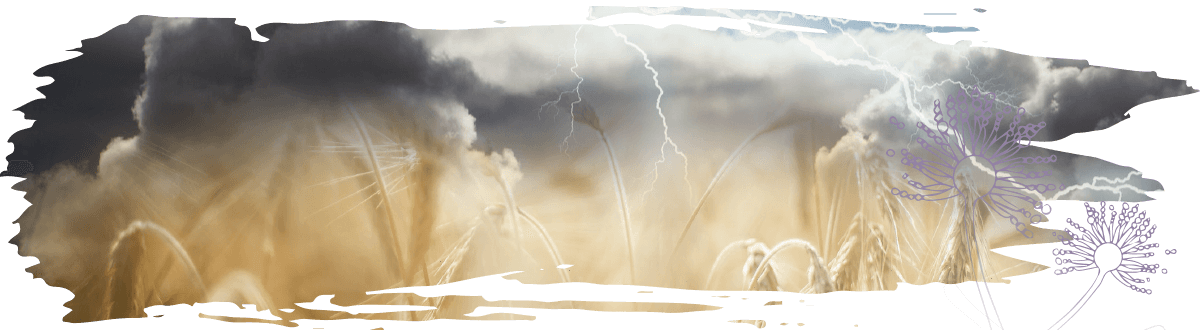

How are periods of prolonged drought and heat waves affecting the dynamics of toxin-producing species?

In general, mycotoxin-producing fungi are favored by warmer temperatures and drought.

⇒ These conditions are not only good for fungal growth, but also weaken plants, making them more susceptible to colonization by fungal species.

This is aggravated when periods of high temperatures are accompanied by episodes of intense rainfall that increase the ambient humidity.

What strategies do you consider key for university research on mycotoxins to have a real impact on the agri-food industry?

This is the great Achilles heel we have at the University.

We are capable of discovering many things and proposing effective methods for mycotoxin control, but not of transferring our knowledge to companies.

We are capable of discovering many things and proposing effective methods for mycotoxin control, but not of transferring our knowledge to companies.

In my opinion, it is a problem on both sides:

- ⇒ At the University we like research very much and we tell our scientific colleagues about it in articles or at congresses. However, it is very difficult for us to reach industry, it seems that we speak different languages.

- ⇒ Many companies also do not take the step to look for research groups to help them with the problems they need to solve.

This lack of two-way communication means that much of the development that is achieved at the University is never transferred to the agri-food sector and, of course, that is something that has to change.

This lack of two-way communication means that much of the development that is achieved at the University is never transferred to the agri-food sector and, of course, that is something that has to change.

If you had to prioritize one line of research for the next 10 years in this field, what would it be and why?

Much of my research is focused on the development of methods to control the presence of mycotoxins in food and therefore has a clear practical focus.

However, I am a strong advocate of what we call basic science:

We need to understand how fungi can produce toxins and what factors influence this process.

We need to understand how fungi can produce toxins and what factors influence this process.

- ⇒ In this way, we can be more effective in optimizing new control methods.

We need to study the current distribution of fungal species in the context of climate change to understand the new risks associated with mycotoxins.

We need to study the current distribution of fungal species in the context of climate change to understand the new risks associated with mycotoxins.

Micotoxicosis prevention

Micotoxicosis prevention